Permanent tribunal to adjudicate on inter-state disputes

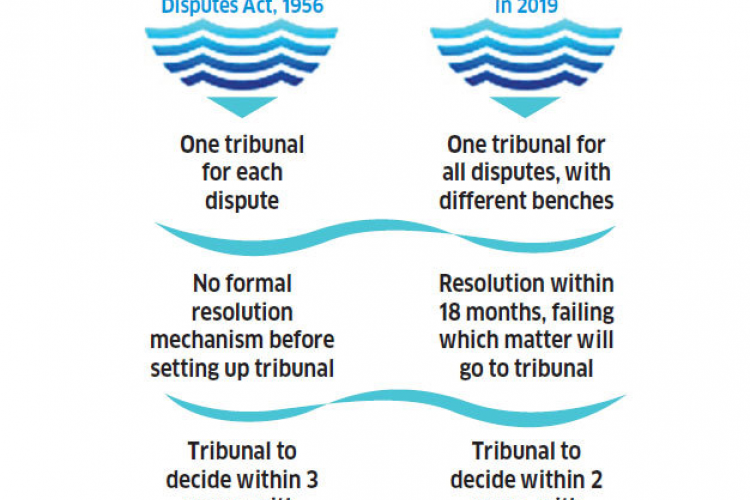

Lok Sabha gave its approval to a proposal to set up a permanent tribunal to adjudicate on inter-state disputes over sharing of river waters. The Bill cleared by Lok Sabha seeks to make amendments to the Inter-State River Waters Disputes Act of 1956 that provides for setting up of a separate tribunal every time a dispute arises. Once it becomes law, the amendment will ensure the transfer of all existing water disputes to the new tribunal. All five existing tribunals under the 1956 Act would cease to exist.

Why the change ?

The main purpose is to make the process of dispute settlement more efficient and effective. Under the 1956 Act, nine tribunals have so far been set up. Only four of them have given their awards. One of these disputes, over Cauvery waters between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, took 28 years to settle. The Ravi and Beas Waters Tribunal was set up in April 1986 and it is still to give the final award. The minimum a tribunal has taken to settle a dispute is seven years, by the first Krishna Water Disputes Tribunal in 1976.

The amendment is bringing a time limit for adjudicating disputes. All disputes would now have to be resolved within a maximum of four-and-a-half years.

The multiplicity of tribunals has led to an increase in bureaucracy, delays, and possible duplication of work. The replacement of five existing tribunals with a permanent tribunal is likely to result in a 25 per cent reduction in staff strength, from the current 107 to 80, and a saving of Rs 4.27 crore per year.

The current system of dispute resolution would give way to a new two-tier approach. The states concerned would be encouraged to come to a negotiated settlement through a Disputes Resolution Committee (DRC). Only if the DRC fails to resolve the dispute will the matter be referred to the tribunal.

How it will work?

In the existing mechanism, when states raise a dispute, the central government constitutes a tribunal. Under the current law, the tribunal has to give its award within three years, which can be extended by another two years. In practice, tribunals have taken much longer to give their decisions.

Under the new system, the Centre would set up a DRC once states raise a dispute. The DRC would be headed by a serving or retired secretary-rank officer with experience in the water sector and would have other expert members and a representative of each state government concerned. The DRC would try to resolve the dispute through negotiations within a year and submit a report to the Centre. This period can be extended by a maximum of six months.

If the DRC fails to settle the dispute, it would be referred to the permanent tribunal, which will have a chairperson, a vice-chairperson and a maximum of six members — three judicial and three expert members. The chairperson would then constitute a three-member bench that would consider the DRC report before investigating on its own. It would have to finalise its decision within two years, a period that can be extended by a maximum of one more year — adding up to a maximum of four-and-a-half years.

The decision of the tribunal would carry the weight of an order of the Supreme Court. There is no provision for appeal. However, the Supreme Court, while hearing a civil suit in the Cauvery dispute, had said the decision of that tribunal could be challenged before it through a Special Leave Petition under Article 136 of the Constitution.

"UPSC-2026-PRELIMS COMBINED MAINS FOUNDATION PROGRAMME" STARTS WITH ORIENTATION ON FEB-10

"UPSC-2026-PRELIMS COMBINED MAINS FOUNDATION PROGRAMME" STARTS WITH ORIENTATION ON FEB-10